What the NBA Can Teach You About Your MBA

The demands of running a tech company are different from the demands of running a traditional company, like a bank or a clothing company. And managing engineers and scientists is very different from managing accountants or lawyers. In fact, managing tech companies is a lot like managing basketball teams, in today’s complex, data-driven world.

Managers in both worlds need to be able to manage incredibly complex data in a fast-changing environment, in order to identify and act on opportunities. Sometimes those opportunities are easy to see, but sometimes they are not. Good managers can make or break a company, depending on how they deal with fast-moving markets, complex products and a rapidly changing knowledge base. Or...as the case may be, identifying the best basketball player to trade for your team.

The No-Stats All-Star

Take Shane Battier. Ever heard of him? He played for the Houston Rockets, the Miami Heat and the Memphis Grizzlies during his career (now retired). A lot of people still don’t realize who he is. There are no stats on Shane Battier as being one of the “best” players in the N.B.A. He never shows up in best-player-of-all-time lists. During his career, he was widely regarded as playing sound, fundamental, team-oriented basketball.

However, many people now consider Shane Battier one of the most important players in the recent history of the game. Shane is a two-time NBA champion and an NCAA champion, and what’s really interesting about Shane is that whenever he was on court during his 13 year N.B.A. career, his team performed better…and when he was off the court, his team performed worse. He had an almost supernatural ability to confer winningness on the teams he played with.

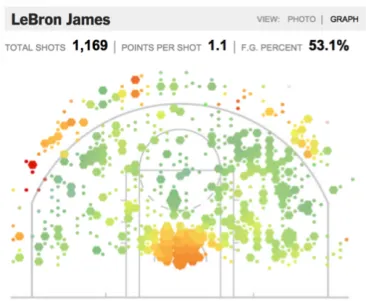

If basketball managers had been able to identify this quality during Battier’s career, he would have been one of the most hotly contested players in the league. But this kind of stat is difficult to quantify. Michael Lewis, the author of The Blindside and Moneyball has referred to Shane as the “No Stats All-Star”. This is because Shane has a unique ability: he can force opponents into their zones of least efficiency very well. It doesn’t matter who they are. They can be the best players in the game: Kobe Bryant, LeBron James—Shane can push them into positions on the court from which they are statistically unlikely to score. Battier is just uncannily good at reading stats and knowing where these players are likely to miss shots. His genius is pushing those players to the zone of least efficiency and then sitting back and watching them miss their shots.

Heat Map of Le Bron James’ preferred shooting positions. Le Bron’s athleticism and ball-handling create a lot of high percentage points near the basket. His midrange game is weakest--this is his zone of least efficiency. Size of bubble: How much he prefers to take shots from that position Color: Red, orange, yellow; more likely to make the shot, green, less likely.

What this means for the game of basketball is that when Shane was on court, his team played like a championship team. When he was injured or off-court, they just looked like a run of the mill team.

The problem for managers is that this mysterious ability of Shane Battier is something that had simply never been on anyone’s radar as a metric to capture statistically: the measure of forcing players into their zone of least efficiency. Now that Shane has shown them the way, however, some coaches and managers have begun to pay attention to this kind of information, and other pieces of information outside traditional stats, and this is allowing them to start to tap into identifying players like Shane Battier, who, frankly, had just been overlooked before.

Today, savvy basketball managers are trying to capture data to discover players like Shane and also to discover vulnerabilities in other players so they can coach their teams to play more like Shane.

So, data is changing the way basketball gets played. It’s not that the data didn’t exist before, we just didn’t capture it or have good tools to visualize it. Now those tools are starting to exist and managers are starting to get insights that affect how the game is played and how they manage.

Same deal in technology management. Without the free throws.

In Technology Management, as in the world of basketball, we’re beginning to have access to data that we’ve never been able to capture before. The availability and visibility of that data is shifting management practices and product development operations. Understanding these dynamics can radically affect how we manage technical companies.

I worked with General Motors for a number of years and saw firsthand the power of using data to manage technology development and empower innovation for maximal success. One of the best examples I ever saw was when I studied a group of Indian automotive performance engineers who became innovation superheroes at GM.

The Best, Worst Unit at GM

This is the story of how the “worst” unit in GM, actually became the best at innovation, creating more global best practices in a single year than anyone else. And it’s a story of how tapping into data enabled the managers at GM to build and sustain that trend over the long term.

In 2003 a unit was created in India to basically act as a backup unit, providing support on any product, from any global GM team that needed help. The unit had a huge number of new, inexperienced engineers, and people all over the world were sending all their absolute worst work to this team in India--dumping their most difficult, intractable products and problems on them and watching them squirm.

But then, in 2008, something funny happened when GM looked at their process innovation stats. GM evaluates process innovation by country each year. Engineers all around the world discover better ways to engineer product, and if engineers discover a way to reduce the time and cost of development, GM sanctions their ideas as a global best practice. When GM looked at the global innovation data in 2008, the Indian engineers had far outpaced everyone on process innovations – a mere 5 years after this team was created. They had more new ideas to improve product development than anyone else on the entire planet. Something profound had happened, but what?

In the same way that the basketball world was scratching its head trying to figure out why Shane Battier’s teams always won, GM needed to know--and fast--and the answer was to be found in the data.

By analyzing the data, GM’s managers were able to eventually figure out that all of the Indian team’s innovation had come from a particular group of consultants who were getting jobs from all over the world every day, which allowed them to spot process loopholes that needed plugging. This group was on innovation overdrive—they could rapidly make meta-analyses and arrive at global best practices without even trying. They were wildly successful.

There was just one problem. The burn out rate was incredibly high and this led to a drop in innovation over the next couple of years that was almost as precipitous as the original increase.

When the GM managers dug deeper, they discovered the problem. The Indian engineers hated being consultants. They felt no one valued their work, because they didn’t own a product. They didn’t have the ability to see long term ideas come to fruition, because they kept being moved from project to project. Local management, in response, had moved all these unhappy consultants to team-based remote assignments working with engineers from a single country. They had done this based on routine management practices, and without really looking at the data or thinking about the underlying patterns. That’s why innovation had dropped precipitously: because now there were no longer any consultants who could see the global patterns and do the meta-analyses that led to process insights.

Eventually, this story has a happy ending because the local managers started listening to the data and connecting the dots and figuring out how to manage their teams better.

In response, they moved engineers back into the global consulting role, but with some important changes. They gave them incentives, they gave them ownership in their work and the company valued their contributions. The consultants got recognized for their unique role in process innovation. The entire culture shifted to one of valuing process. Engineers rotated from projects to consulting and back again to prevent burn out. There was a massive cultural change. And guess what? The rate of innovation started to rise again.

Shane Battier and the Indian super-innovators are just two examples of how, on basketball teams and at technology companies, data is deeply shaping the way management is done most effectively.

In the fast-paced world of technology development, and in sports, alliances and networks are extremely important. There is a global talent base and the situation is changing all the time. The increasing availability of data and information to shape decisions is becoming absolutely critical to managing the ways that people work together on teams.

To be most effective at managing technology companies, managers need to keep their eyes not just on the standard metrics, but also on emerging data and new metrics, which are being discovered every day. They need to visualize them in new ways that enable practical insights and better decision-making. Managers who do this are profoundly changing the way the game is played, for the better.

--The Master of Technology Management (MTM) program at UC Santa Barbara is designed to catapult engineers and scientists into leadership positions — within both startups and established companies. This 9-month, intensive program is designed to teach the frameworks, skills, and techniques you need to be a successful technology manager. No fluff, no filler. The MTM degree will get you further, faster.

Instagram

Instagram LinkedIn

LinkedIn Twitter

Twitter